by Keith Harmoney, Range Scientist, Hays

Over the years, I’ve heard rangeland managers develop rules of thumb, or short phrases, to try to help them simplify decisions that need to be made to manage their pastures. Some of these rules of thumb have merit and scientific or economic data to support the rules of thumb; however, some rules of thumb may be unfounded and lack informational support. In the previous Beef Tips Newsletter, I listed some common rules of thumb, along with an explanation of whether or not the rule of thumb has any merit or basis of support. You can go back and read the first four Rules of Thumb in the January Beef Tips. This month, another four Rules of Thumb are listed, and a Thumbs Up means it’s a rule of thumb with merit, and a Thumbs Down indicates the rule of thumb lacks support and has room for improvement. A Thumbs Up and a Thumbs Down means that arguments may be made for and against the rule of thumb.

Don’t be overgrazed and understocked. Thumbs Up. This rule mainly addresses livestock distribution and pasture usage. Pastures may develop some locations that receive heavy usage and low forage availability, yet in the same pasture some locations may have little or no forage usage with abundant available forage. Three main reasons allow for pastures to develop this condition. First, watering locations may inhibit animals from traveling to the farthest reaches of a pasture and restricts them to spend more time grazing near the water source. Large pastures where animals have to walk more than one-half to one mile to water, depending on terrain, will limit how far animals can travel to graze. Water is a greater necessity, so animals will spend most of their time within a mile of the watering source with level topography, and even closer in rough topography. Second, pastures with odd features, such as an unconventional pasture shape or odd landscape features, may restrict where animals travel. Changing the shape of a pasture to be more square will help to promote more even use. Third, pastures with a history of continuous stocking with no change in management, such as altered season of use, growing season rest period, or prescribed fire, may allow animals to construct grazing lawns of greater use and high quality regrowth, and at the same time form patches of avoided wolf plants that change little from year to year. Adding watering locations to remote pasture areas, changing fence boundaries to force animals to stay in particular sections of a pasture, and prescribed burning underused areas are three of the most assured ways to change where animals graze. Other practices can attract animals to less used portions of a pasture, such as salt and mineral or supplement and protein tub placement, mowing low use sections of a pasture, and spraying certain herbicides or molasses to enhance quality or taste. However, it is important to note that managers with a heavy focus on wildlife habitat may appreciate the diverse plant structure of uneven grazing animal distribution as it may attract a diverse population of grassland birds that have preferences for either short vegetation or tall and dense vegetation.

Don’t be overgrazed and understocked. Thumbs Up. This rule mainly addresses livestock distribution and pasture usage. Pastures may develop some locations that receive heavy usage and low forage availability, yet in the same pasture some locations may have little or no forage usage with abundant available forage. Three main reasons allow for pastures to develop this condition. First, watering locations may inhibit animals from traveling to the farthest reaches of a pasture and restricts them to spend more time grazing near the water source. Large pastures where animals have to walk more than one-half to one mile to water, depending on terrain, will limit how far animals can travel to graze. Water is a greater necessity, so animals will spend most of their time within a mile of the watering source with level topography, and even closer in rough topography. Second, pastures with odd features, such as an unconventional pasture shape or odd landscape features, may restrict where animals travel. Changing the shape of a pasture to be more square will help to promote more even use. Third, pastures with a history of continuous stocking with no change in management, such as altered season of use, growing season rest period, or prescribed fire, may allow animals to construct grazing lawns of greater use and high quality regrowth, and at the same time form patches of avoided wolf plants that change little from year to year. Adding watering locations to remote pasture areas, changing fence boundaries to force animals to stay in particular sections of a pasture, and prescribed burning underused areas are three of the most assured ways to change where animals graze. Other practices can attract animals to less used portions of a pasture, such as salt and mineral or supplement and protein tub placement, mowing low use sections of a pasture, and spraying certain herbicides or molasses to enhance quality or taste. However, it is important to note that managers with a heavy focus on wildlife habitat may appreciate the diverse plant structure of uneven grazing animal distribution as it may attract a diverse population of grassland birds that have preferences for either short vegetation or tall and dense vegetation. What you see aboveground is what you get belowground. Thumbs Up. Rangeland grasses prioritize leaf growth to perform their main function, capturing sunlight for photosynthesis and manufacturing carbohydrates. Once plants have achieved vigorous leaf growth for photosynthesis and produced excess sugars not used for producing more leaves, plants will continually use those excess sugars as carbohydrate building blocks for developing and growing more roots. Grasses with abundant aboveground biomass or yield will also have an abundant root system. More than half of a grass plants total biomass is actually belowground in the root system. Grasses that are constantly defoliated and produce little aboveground biomass will have shorter root systems that extract water and nutrients from a smaller volume of soil. Grasses that are utilized heavily with little aboveground growth also offer less protection for the soil and allow greater water runoff and less water infiltration. In a study that compared heavy pasture utilization to light pasture utilization, water infiltration rates were nearly two times greater in the lightly utilized pasture with greater aboveground biomass and soil cover. Because of these two characteristics, extracting water from less soil volume and capturing less precipitation, pastures with heavy utilization can create their own drought occurrence even in the midst of an average year of precipitation.

What you see aboveground is what you get belowground. Thumbs Up. Rangeland grasses prioritize leaf growth to perform their main function, capturing sunlight for photosynthesis and manufacturing carbohydrates. Once plants have achieved vigorous leaf growth for photosynthesis and produced excess sugars not used for producing more leaves, plants will continually use those excess sugars as carbohydrate building blocks for developing and growing more roots. Grasses with abundant aboveground biomass or yield will also have an abundant root system. More than half of a grass plants total biomass is actually belowground in the root system. Grasses that are constantly defoliated and produce little aboveground biomass will have shorter root systems that extract water and nutrients from a smaller volume of soil. Grasses that are utilized heavily with little aboveground growth also offer less protection for the soil and allow greater water runoff and less water infiltration. In a study that compared heavy pasture utilization to light pasture utilization, water infiltration rates were nearly two times greater in the lightly utilized pasture with greater aboveground biomass and soil cover. Because of these two characteristics, extracting water from less soil volume and capturing less precipitation, pastures with heavy utilization can create their own drought occurrence even in the midst of an average year of precipitation. 60% of pasture growth occurs by July 1. Thumbs Up. Rangelands across Kansas are dominated by native, warm-season grasses. Basically, this means that these grasses and pastures grow best under warm conditions. When air temperatures climb and soil temperatures reach above 55⁰ F, warm-season grasses will begin to break their winter dormancy and will begin rapid growth at soil temperatures over 65⁰ F. This will usually occur close to mid-April in the eastern portion of the state and the first of May in the western part of the state. Growth is slow until air temperatures climb into the 70’s and 80’s. By the end of May, about 30% of the total growth for the year has developed (Figure 1, growth summaries from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Ecological Site Descriptions).

60% of pasture growth occurs by July 1. Thumbs Up. Rangelands across Kansas are dominated by native, warm-season grasses. Basically, this means that these grasses and pastures grow best under warm conditions. When air temperatures climb and soil temperatures reach above 55⁰ F, warm-season grasses will begin to break their winter dormancy and will begin rapid growth at soil temperatures over 65⁰ F. This will usually occur close to mid-April in the eastern portion of the state and the first of May in the western part of the state. Growth is slow until air temperatures climb into the 70’s and 80’s. By the end of May, about 30% of the total growth for the year has developed (Figure 1, growth summaries from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service Ecological Site Descriptions).

Figure 1. Monthly and cumulative projected forage growth from USDA NRCS ecological site descriptions. Continually warming temperatures combined with ample soil moisture produce continued rapid warm-season grass growth. Another 30% of the total pasture growth for the year typically occurs in June, so as much growth usually occurs in June as during the months of April and May combined. This is especially true in June for grass species that have started elongated stem growth in preparation for producing seed heads. Cool-season grasses begin rapid growth approximately one month prior to warm-season grasses, so rangelands that have any native cool-season grass species also present will have an even greater percentage of the years grass growth produced by July 1. By the end of July, many grasses have fully developed leaf canopies and have fully developed seed heads, so nearly 85% of the year’s total forage has been produced.

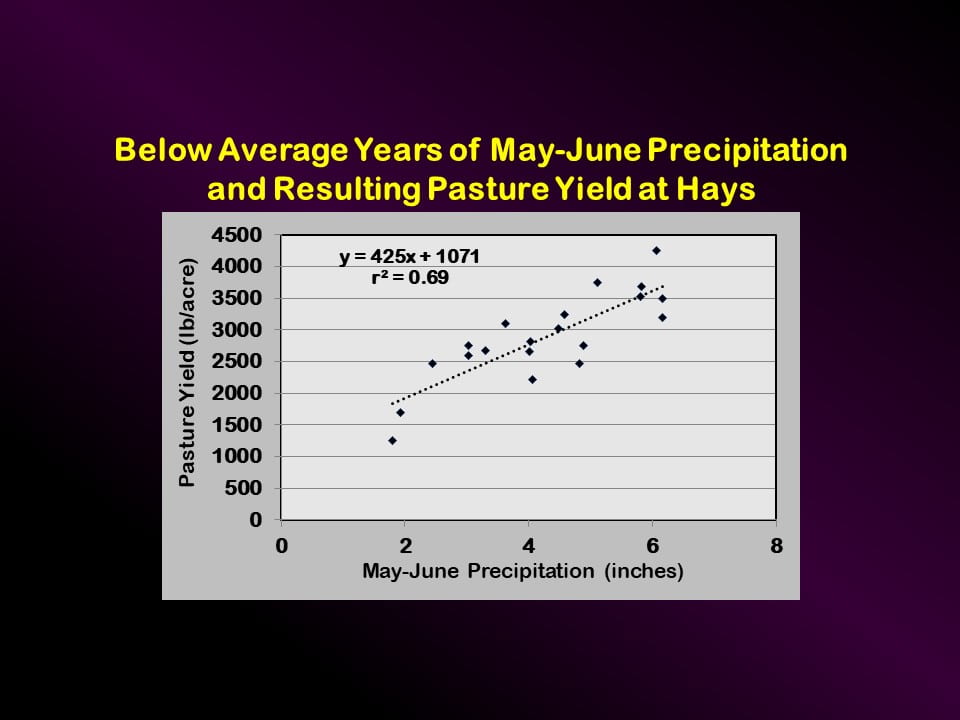

Wet winters produce more grass. Thumbs Down. At the start of each grazing season, producers are usually trying to predict how much forage will be produced during the year so that they can set proper stocking rates for pasture. Many use the amount of winter precipitation received as the basis for predicting yield at the end of the growing season. However, forty years of weather data and pasture yield data in western Kansas show that winter precipitation has no relationship with pasture yield and is a poor predictor of end of year total forage production. The best early predictor for end of year pasture yield is the total accumulation of May and June precipitation. This makes sense because the two months with the greatest amount of grass growth are also May and June. A recent summary of several central and northern Great Plains research locations also showed that May and June precipitation combined is the best early predictor of annual pasture yield. This is especially true when rainfall is below average in western Kansas. For example, average long-term May-June precipitation at Hays is 6.2 inches, and average long-term pasture yield at this research site is just under 3400 lb/acre. When precipitation is below average, pasture yields have a direct linear relationship with May-June rainfall (Figure 2). So, in dry springs, the amount of forage produced for this site can be predicted by precipitation received.

Wet winters produce more grass. Thumbs Down. At the start of each grazing season, producers are usually trying to predict how much forage will be produced during the year so that they can set proper stocking rates for pasture. Many use the amount of winter precipitation received as the basis for predicting yield at the end of the growing season. However, forty years of weather data and pasture yield data in western Kansas show that winter precipitation has no relationship with pasture yield and is a poor predictor of end of year total forage production. The best early predictor for end of year pasture yield is the total accumulation of May and June precipitation. This makes sense because the two months with the greatest amount of grass growth are also May and June. A recent summary of several central and northern Great Plains research locations also showed that May and June precipitation combined is the best early predictor of annual pasture yield. This is especially true when rainfall is below average in western Kansas. For example, average long-term May-June precipitation at Hays is 6.2 inches, and average long-term pasture yield at this research site is just under 3400 lb/acre. When precipitation is below average, pasture yields have a direct linear relationship with May-June rainfall (Figure 2). So, in dry springs, the amount of forage produced for this site can be predicted by precipitation received.

Figure 2. Relationship of May-June precipitation and pasture yield at Hays, KS. A similar reduction in the percentage of average production is likely present for other western Kansas sites. For drought planning, predicting end of season forage production by the end of June is important to plan for stocking rate reductions. Because the growing season tends to be longer in eastern Kansas, precipitation in May, June, and July are the key months for determining end of season yield. Winter precipitation helps set the stage for pastures to begin spring growth, but precipitation that falls later in May and June (and July in eastern Kansas) actually has the greatest impact on how much forage is eventually produced.

Look for the next round of Rules of Thumb for Grazing Management in the next Beef Tips.