“What’s Your Cost of Production?”

By: Justin Waggoner, Ph.D., Beef Systems Specialist

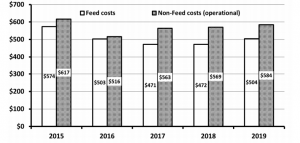

I can assure you that Henry Ford knew exactly how long and how much it cost to produce the Model T. Although it may seem difficult to make comparisons between the automotive industry and modern day beef production, many cow‐calf operations are business enterprises…large business enterprises. Yet financial benchmarking and accurately documenting production costs are not necessarily high on the “to do” list of most cattle producers. One of the best reasons to know what it costs to produce a calf or what your total feed and non‐ feed costs are is that it allows you to quickly evaluate emerging opportunities such as grazing a neighbor’s cover crop or an additional circle of corn stalks. Thus, if you don’t know your production costs, I would encourage you to think about them. Tax time is a great time to take a good look at your business and calculate your production costs. If you would like to get a better idea of what it costs to produce a calf in Kansas, the Kansas Farm Management Association (KFMA) Enterprise Reports provide that information in a one page summary that can be accessed on the Ag Manager website (https://www.agmanager.info/kfma). The chart below shows the total feed and non‐feed (operational) costs of KFMA participating cow‐calf producers from 2015 to 2019.

The data from these operations suggests that in 2019, feed costs were approximately $504 per cow and the non‐feed or operational costs were approximately $584 per cow. Thus, the average total cost to produce a calf was $1088 ($504 + $584) on these operations in 2019. The total feed costs (pasture and purchased feed) of $504 amounts to $1.38 per day to feed a cow in Kansas. The question is “What does it cost you to feed a cow and produce a calf?”

For more information, contact Justin Waggoner at jwaggon@ksu.edu.