“The Basics of Mineral Nutrition”

By Justin Waggoner, Ph.D., Beef Systems Specialist

Most beef cattle producers recognize that mineral nutrition is important. However, a mineral program is only one component of an operation’s nutrition and management plan. An exceptional mineral program will not compensate for deficiencies in energy, protein or management. Additionally, the classical signs associated with clinical deficiency of a particular mineral (wasting, hair loss, discoloration of hair coat, diarrhea, bone abnormalities etc.) are not often or are rarely observed in production settings. The production and economic losses attributed to mineral nutrition in many situations are the result of sub-clinical deficiencies, toxicities and antagonisms between minerals which are often less obvious (reduced immune function, vaccine response, and sub-optimal fertility). The figure below, adapted from Wikse (1992), illustrates the effect of trace mineral deficiency on health and performance and the margin between adequate mineral status and clinical deficiency.

Many producers erroneously assume that the science of mineral nutrition is relatively complete. However, mineral nutrition is complicated and our knowledge of mineral nutrition is actually relatively incomplete. There are 17 minerals required in the diets of beef cattle. However, no requirements have been established for several minerals that are considered essential (Chlorine, Chromium, Molybdenum, and Nickel). Minerals may be broken down into two categories. 1. The macrominerals whose requirements are expressed as a percent of the total diet (calcium, phosphorous, magnesium, potassium, sodium, chlorine and sulfur). 2. The microminerals or trace minerals (required in trace amounts) whose requirements are expressed as parts per million (ppm) or milligrams per kilogram of dry matter consumed (chromium, cobalt, copper, iodine, iron, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, selenium and zinc).

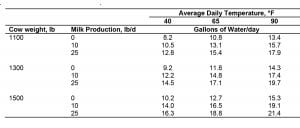

Mineral status of an animal is a function of the total diet (both water and feed) and stored mineral reserves within the body. Water may be a substantial source of mineral; however the variation in water consumption, makes estimating the contribution of mineral from water sources difficult. Mineral content of forages is influenced by several factors including plant species, soil, maturity, and growing conditions. These factors, and others not mentioned, makes estimating the dietary mineral content of grazing cattle challenging. Most commercial mineral supplements are formulated to meet or exceed the requirements for a given stage of production. This ensures that deficiencies are unlikely, but providing supra-optimal levels of minerals may be unnecessary unless specific production problems exist. A mineral program does not have to be complex or expensive to be successful. Minerals are an important component of beef cattle nutrition that should not be over-looked as sub-clinical deficiencies of minerals likely contribute to more production and economic losses than we realize. For more information, contact Justin Waggoner at jwaggon@ksu.edu.