The New Year often brings with it some of the coldest months of the year.

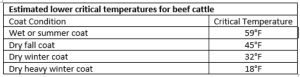

Cattle are most comfortable within the thermonuetral zone when temperatures are neither too warm nor cold. During the winter months cattle experience cold stress anytime the effective ambient temperature, which takes into account wind chill, humidity, etc., drops below the lower critical temperature. The lower critical temperature is influenced by both environmental and animal factors including hair coat and tissue insulation (body condition). The table below lists the estimated lower critical temperatures of cattle in good body condition with different hair coats. In wet conditions cattle can begin experiencing cold stress at 59°F, which would be a relatively mild winter day. However, if cattle have time to develop a sufficient winter coat the estimated lower critical temperature under dry conditions is 18°F. Cold stress increases maintenance energy approximately 1% for each degree below the lower critical temperature, but does not impact protein, mineral or vitamin requirements. Thus, maintenance energy requirements of cattle may increase by 15-20% on those exceptionally cold and windy days that commonly occur in January and February. Increased maintenance energy requirements essentially means that less energy is available for production (gain), which translates to lower ADG, increased Feed:Gain, and greater Days on Feed.

The Kansas State University Mesonet now has an animal comfort feature that provides an index of animal comfort (heat and cold stress) for current condition as well as 7-day forecast. The Mesonet allows users to see both statewide maps and select specific weather stations across the state. The animal comfort page of the Kansas Mesonet may be accessed at https://mesonet.k-state.edu/agriculture/animal/current/.

For more information, contact Justin Waggoner at jwaggon@ksu.edu