by A.J. Tarpoff DVM, MS. Beef Extension Veterinarian

Neonatal calf scours (diarrhea) is a multifactorial issue. The risk and occurrence can change year to year based on many different factors. Due to the cold, wet and windy weather of late, it sets up for some unique challenges in combating calf scours this year.

Causes

Scours can be initiated by infectious agents such as viruses, bacteria, and even protozoan parasites. It is important to note that most of the pathogens of concern are shed at low levels through the feces by healthy members of the resident cowherd. Most of the disease and death loss related to scours occurs within the first month of age. The bacteria, E. coli, is a common culprit within the first 5 days of life. Rota virus, Corona virus, and cryptosporidium (protozoa) are commonly identified in cases between 1 week and 3 weeks of age. Mixed infectious with more than 1 pathogen commonly occurs as well. Salmonella and Clostridial infections can also occur with minimal clinical signs before acute death.

Nutritional causes of neonatal diarrhea can also occur. “Milk Scours”, as it is often referred to, is a non-infectious cause of white loose manure. This tends to occur after a cow/calf separation event. The hungry calves tend to over eat leading to undigested milk passing through the digestive tract. The intestinal disruption is often self-limiting and clears up within a day or two without treatment.

Clinical Signs

The most common clinical signs of calf scours are watery stool, lethargy, and dehydration.

- Diarrhea: The color of the stool can be brown, green, yellow, or grey in color. Tail and the rear legs may be covered in wet manure. Bloody stools can also be seen with Salmonella, Clostridial, or coccidiosis.

- Lethargy: noted by decreased desire to nurse, depressed attitude, and reluctance to stand. Staggered walk may also occur.

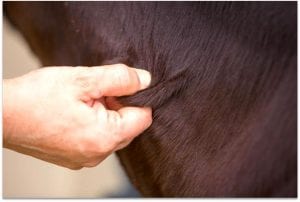

Tenting skin to test for dehydration. Photo courtesy of Dr. Gregg Hanzlicek - Dehydration: identified by having sunken eyes. Another effective means to measure dehydration is by tenting the skin of the calf. A well hydrated calf’s skin will snap back flat after pinching it. if it takes 1-3 seconds, the calf would be ~6-8% dehydrated. If the skin tent takes up to 5 seconds, the calf would be ~8-10% dehydrated.

- The severe loss of fluids also interrupts the calf’s acid/base and electrolyte balances

Treatment

The most important thing to do when deciding how to treat calf scours is to work with a local veterinarian. They have the expertise to help guide producers through the process on how to intervene to give the best chance for calf survival. Treatment of calf scours is directed toward correcting the main issues: Dehydration, Acid/Base imbalance, and Electrolyte imbalance. Fluid therapy is typically the first step in scour treatment. This is usually carried out through oral electrolytes and fluids to correct the dehydration and continued loss. There are many electrolyte formulations available on the market. Not all formulations are the same. They are formulated for many different purposes depending on electrolyte, energy, and pH buffering needs. Selection decisions of these products should be made with the input of a veterinarian. Always follow label directions when mixing and administering electrolyte solutions. However, if the calf is severely dehydrated IV fluids administered by a veterinarian offers the best chance to recovery. Many times the calves lose their ability to maintain proper body temperature. Supportive care through thermal support during the course of disease may help increase calf vigor, desire to suckle, and mentation. Veterinarians may also include oral or systemic antibiotics in certain cases when it has been determined to be bacterial cause, or septicemia is a concern.

Possible treatment procedures should be discussed with a veterinarian before the calving season begins. Having a basic inventory of supplies and products as well as a protocol in place will ensure proper early treatment in the course of the disease.

If treatment response is poor, or if there is abnormally high incidence of disease, further diagnostics from a necropsy and results from a Veterinary Diagnostic Lab will help with proper treatment regimens.

Prevention

Regardless of the pathogen(s) involved, there are some basic management strategies to reduce the risk of developing an outbreak. Four key areas to concentrate on are biosecurity, supporting proper immune function, environmental management, and hygiene.

Biosecurity:

It is imperative to not inadvertently introduce disease into an operation. But it is something that is often overlooked. If a new calf or cow from outside the herd is introduced during or around calving season (30 days before/30 days after), ensure that those individuals are quarantined and separated from the rest of the herd. This often happens when we graft a sale barn calf onto a cow that lost its calf, or purchase a milk cow to nurse an orphan. Any animals from outside your herd can introduce this devastating disease to your operation.

Sick animals (especially scouring calves) can shed enormous amounts of pathogens into the environment. Isolating these animals and eliminating any mingling of infirmed animals and newborns will greatly reduce the exposure risk to new born calves.

Immune Function:

Calf hood immune protection all starts with the first critical meal known as colostrum. Ensuring adequate intake and suckling behavior of the freshly born calf is important. Intake within the first few hours of life will increase the efficiency of colostrum antibody transfer into the calf. But colostrum quality all stems back to care of the cow. Previous research has shown proper nutritional supplementation to maintain Body Condition Score (BCS) will help increase both colostrum quality and quantity in the dam. Vaccination status of the dam can also play a critical role in calf health. Boosting immune function will transfer a higher level of antibody to those pathogens into the colostrum.

Environment:

The solution to pollution is dilution! Reducing the environmental contamination of pathogens that new born calves are exposed to is a great way to reduce the risk of scours. These pathogens build up in the environment where cattle are housed for extended periods of time. An excellent program to reduce the contamination and risk of the disease is the Sandhills Calving System. The principles behind this system are 2-fold. First, calves born earlier in the calving season are exposed to smaller amounts of pathogens. Because of this, they typically do not break with disease. However, they do act as disease amplifiers. They will shed pathogens at a much higher rate., Separating calves by age group decreases the risk of exposure due to environmental contamination. Second, is limiting accumulation of pathogens on the calving ground, by calving in a “clean” area. These principles are put into practice by calving in 1 pasture or paddock for about 2 weeks. Then moving still pregnant cows to a new calving area to calve for another 2 weeks, leaving the cow/calf pairs in the first pasture. Continue until the youngest calf is a month of age, then the animals can be managed as one group again. The theory is sound, and in practice can work quite well. Unfortunately, many operations do not have the cross fencing, water access or space availability to manage this. But, any movement to break the disease cycle can make a major impact on the course of the disease. By understanding these principles of separation and minimizing contamination, several steps can be taken to mitigate the risk. Utilizing pregnancy check data, operations can split herds into calving groups to be managed in different pastures. This will decrease overall contamination in the pasture settings. Rotating feeding and resting areas throughout the pasture can also dilute the amount of contamination that newborn calves are exposed to. This may include utilizing portable windbreaks or shelters, rolling hay in different locations or moving hay feeders as the season progresses.

If a single calving area is utilized on the operation, strict management may be necessary to mitigate risk. Cows and newborn calves should be turned out into a “clean” pasture as soon as possible after birth. Ideally the pasture of choice should be filled with cows with calves of roughly the same age.

Barns and chute areas used to intervene during hard calving situations should also be kept clean. These areas also become contaminated through the season. Removing and replacing soiled bedding can reduce the pathogen load. After assisting births, cleaning teat ends of the cow will reduce the exposure of environmental pathogens during the calf’s first suckling opportunity.

Hygiene

Many scour pathogens can cause illness in people, this is known as zoonosis. Personal hygiene is critical to ensure ranchers don’t succumb to the same diarrhea causing bugs as their calves. Washing hands, wearing gloves, and disinfecting equipment can all reduce the chance of sickness.

Hygiene is also critically important to avoid accidental infection of newborn calves through handling and management procedures. Esophageal tube feeders, nursing bottles, gloves, boots, and coveralls can all carry dangerous pathogens from a sick calf to a newborn calf. Use separate tube feeders and equipment for sick calves, and be sure to wash them thoroughly between animals. Work flow is another important concept to consider. Handle sick or infirmed calves after any healthy calves or newborns. This will ensure there it not cross contamination from clothing.