“Got Water…But How Much Do Those Cows Need?”

Justin Waggoner, Ph.D., Beef Systems Specialist

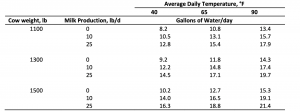

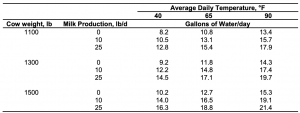

Most cattle producers fully understand the importance of water. After all, providing an adequate supply of clean, fresh water is the cornerstone of animal husbandry and there are very few things that compare to the feeling of finding thirsty cows grouped around a dry tank on a hot day. Water is important, and in situations where the water supply is limited or we are forced to haul water, one of the first questions we find ourselves asking is “how much water do those cows need?” The old rule of thumb is that cattle should consume 1‐2 gallons of water per 100 lbs of bodyweight. Accurately determining the amount of water cows will voluntarily consume is difficult and is influenced by several factors (ambient temperature, moisture and salt content of the diet, body weight, lactation, etc.). Water consumption increases linearly as ambient temperature increases above 40 Fahrenheit such that cows require an additional gallon of water for every 10 degree increase in temperature. Additionally, lactation also directly increases the amount of water required by beef cows. The table below summarizes the daily water requirements of beef cows of several different body weights, milk production levels, and ambient temperatures.

The daily water requirements of beef cows represented are estimates and water consumption varies greatly during the summer months when temperatures exceed 90° Fahrenheit. Therefore, these recommendations should be regarded as minimum guidelines.

For more information, contact Justin Waggoner at jwaggon@ksu.edu.