“Feeding Corn to Cows this Winter”

by Chris Reinhardt, feedlot specialist

Although some areas received abundant rain this summer and have ample hay supplies, other regions received only marginal rains, resulting in a marginal hay crop. On the other hand, most of the corn-growing regions of the Midwest and High Plains had excellent growing and harvest conditions which have contributed to abundant grain supplies, resulting in relatively low corn prices this fall.

This combination of coinciding circumstances have raised the question, “Can I feed corn to cows instead of hay?” Well, the answer is an emphatic, “Maybe…”

Nutritionists look at a cow as essentially a rumen with legs, a mouth, and an udder. The cow has a mouth to feed the rumen—more specifically, to feed the rumen microbes, and the job of the rumen microbes is to feed the cow. For most of a cow’s life she has fed these microbes a diet primarily of cellulose in the form of grass, hay, corn stalks, wheat straw, etc. What little concentrate (grain, by-product feeds, protein supplements) she’s received has been in the form of a small amounts of supplement in addition to the forages which have been her main diet.

The rumen microbes digest the cellulose in forages best when the rumen pH remains in the range of 6.0 to 6.5; this is one (although not the only) reason cows chew their cud: the saliva produced and injected into the cud during rumination contains buffers to keep the pH above 6.0. The more grain or other concentrate feeds we provide, the more likely the rumen pH is to decline below 6.0. The other extreme would be finishing feedlot cattle consuming a high-grain diet which results in a rumen pH in the low 5’s or perhaps even the high 4’s—very acidic. This acidic pH makes for an environment unfavorable for forage digestion.

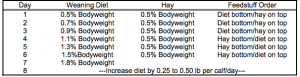

So when we begin to consider feeding more than a small amount of concentrate to cows, we need to consider that the rumen pH will likely fall below the pH which is optimum for forage digestion. For this reason it is advised that we consider feeding a diet which is either less than 25% concentrate (on a dry matter basis), or greater than 75% concentrate, and avoid feeding in between these two levels. Why? Because as we exceed 25% of the diet as concentrate, the rumen pH will decline and the nutritional value of the forages in the diet decline, resulting in wasted expense. (NOTE: this effect becomes more pronounced with increasingly low-quality forages than with high-quality forages.)

A schematic of the results of feeding concentrates in addition to a basal diet of forage looks something like this:

With that out of the way, one way to capture the value of low-cost grains and concentrate feeds this fall and winter, without placing cows on a “finishing” diet, is to consider limit-feeding a high-grain diet. By “high-grain”, we typically mean 70-75% concentrate with sufficient forage to prevent acidosis in aggressive eaters. By “limit-feeding”, we typically mean providing a level of intake of the high-energy diet which supplies a similar total daily amount of energy, protein, minerals, and vitamins, in a smaller intake amount, than we would normally expect when full-feeding a forage-based diet.

For example, you may feed a “conventional”, forage-based winter cow diet of 25 lbs of prairie hay (0.45 Mcal NEM/lb, dry matter basis) with 6 lbs of dried distiller’s grains (0.99 Mcal NEM/lb, dry matter basis), providing a total of 17.3 Mcal NEM per day. This same 17.3 Mcal NEM per animal per day could be supplied from 8 lb cracked corn (1.02 Mcal/lb), 7 lb dried distiller’s grains, and 5 lb of prairie hay. If you’ve done the math, that’s a “conventional”, forage-based diet fed at 31 lbs (dry matter basis) vs. the “limit-fed high-energy” diet fed at 20 lbs. If the cows weigh an average of 1,320 lbs, that’s 2.4% of body weight vs. 1.5% of body weight. FULL DISCLOSURE: the limit-fed cows are going to be hungry and fairly aggressive every morning. Even though they’re receiving the exact same amount of daily energy supply, because they’re not physically full, they will be more than ready come breakfast time. You’ll need stout fences and at 30-36 inches of bunk space per animal in the pen.

There are certainly challenges to limit-feeding cows, most of them pertain to logistics, facilities, and equipment. But two reasons to consider the limit-fed program are: (1) potential per-head feed cost savings; and (2) the chance to reduce the drain on your winter hay stores. In addition, depending on local spot market prices in your area, you may consider inserting other by-product feeds into the high-energy, limit-fed diet, such as: soy hulls, wheat midds, and corn gluten feed, since these all have energy values close to (although not equal to) that of corn.